Sandro Botticelli, original name Alessandro di Mariano Filipepi, was an Italian painter of the Early Renaissance.

Botticelli’s name is derived from that of his elder brother Giovanni, a pawnbroker who was called Botticello (“Little Barrel”). As is often the case with Renaissance artists, most of the modern information about Botticelli’s life and character derives from Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, & Architects, as supplemented and corrected from documents.

He was arguably the best Humanist artist of the Early Renaissance Era, despite the fact that much of his history and inspirations are still obscure to us even in the present.

Botticelli’s posthumous reputation suffered until the late 19th century, when he was rediscovered by the Pre-Raphaelites who stimulated a reappraisal of his work. Since then, his paintings have been seen to represent the linear grace of late Italian Gothic and some Early Renaissance painting, even though they date from the latter half of the Italian Renaissance period.

Botticelli was born in Florence in 1445 AD, his given name being Alessandro di Mariano dei Filipepi. He became known as Botticelli because that was the nickname of his elder brother Giovanni. The future artist’s first work experience was as an apprentice to a goldsmith.

In 1460 Botticelli’s father ceased his business as a tanner and became a gold-beater with his other son, Antonio. This profession would have brought the family into contact with a range of artists. Giorgio Vasari, in his Life of Botticelli, reported that Botticelli was initially trained as a goldsmith.

As a teenager, Botticelli then trained as a painter in the workshop of the Florentine artist and former monk Filippo Lippi who was noted for his frescoes and altarpieces (as well as running off with a nun and having two children with her).

Under the guidance of Fra Filippo Lippi, from 1462, Botticelli created many great artistic works that are all credited to his great master and friend. It is widely accepted that Botticelli learned his artistic finery and skill from Lippi, and it is also believed that he travelled to Esztergom, in Hungary, in order to create a fresco with his master. It is thought that the work was commissioned by the then Archbishop, János Vitéz. During these early years, Botticelli was greatly influenced by Gothicrealism and with all things that were antique.

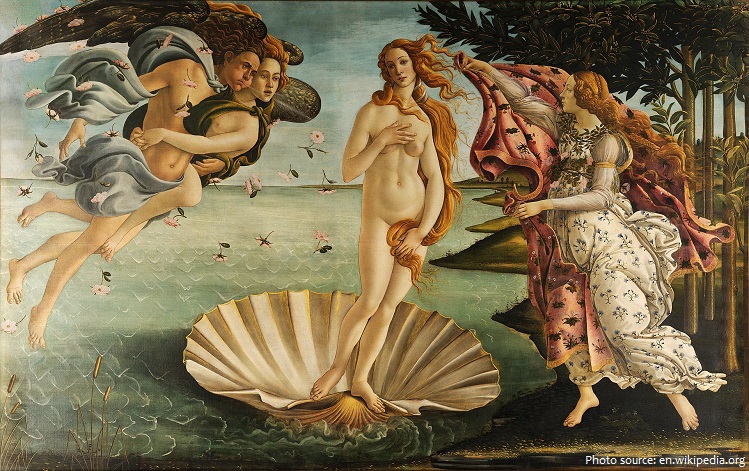

The artist was popular and mixed public works with private commissions, especially for the powerful Medici family of Florence. For the latter, Botticelli explored many themes from Roman and Greek mythology such as the Primavera, now in the Uffizi.

The defining point of Botticelli’s career was the contacts, money and increased fame that grew in abundance at the bequest of the Medici family. The Medici’s were a prominent and wealthy family in Florence and as Botticelli’s fame rose, the family sought him to depict its key members.

The Medici influence propelled Botticelli’s fame to meteoric proportions and as a direct result he was asked by the Papacy to travel to Rome to paint parts of the Sistine Chapel. Such an honor was shared by some of the Renaissance’s greatest artists, such as Ghirlandaio, Perugino and even Michelangelo. Botticelli’s work in Rome included three large pieces and several portraits in the Sistine Chapel itself.

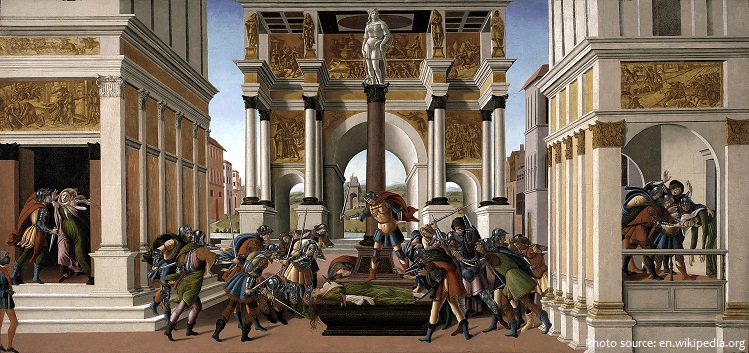

About 1478–81 Botticelli entered his artistic maturity – all tentativeness in his work disappeared and was replaced by a consummate mastery. He was able to integrate figure and setting into harmonious compositions and to draw the human form with a compelling vitality. He would later display unequaled skill at rendering narrative texts, whether biographies of saints or stories from Boccaccio’s Decameron or Dante’s Divine Comedy, into a pictorial form that is at once exact, economical, and eloquent.

The masterpieces Primavera (c. 1482) and The Birth of Venus (c. 1485) are not a pair, but are inevitably discussed together – both are in the Uffizi. They are among the most famous paintings in the world, and icons of the Italian Renaissance. As depictions of subjects from classical mythology on a very large scale they were virtually unprecedented in Western art since classical antiquity. Together with the smaller and less celebrated Venus and Mars and Pallas and the Centaur, they have been endlessly analysed by art historians, with the main themes being: the emulation of ancient painters and the context of wedding celebrations, the influence of Renaissance Neo-Platonism, and the identity of the commissioners and possible models for the figures.

The 1490s was when Botticelli fused the two world of politics and religion on canvas. This was to be the last fifteen years of Botticelli’s short life. This decade was marked with great turbulence and saw the expulsion of the Medici family from Florence life. The entire region was hit by plague and foreign invasions. It was for these reasons, those of the harsh and stark cruelties of life, that Botticelli dismissed the ornamental and intrinsic paintings of his past, instead opting for harsh lines and simplify in his art. It is the paintings that he created towards the end of his career that reflected deep religious themes, that helped him to become elevated, and to be compared to, the great works of Raphael and Michelangelo.

Botticelli had a lifelong interest in the great Florentine poet Dante Alighieri, which produced works in several media. He is attributed with an imagined portrait. According to Vasari, he “wrote a commentary on a portion of Dante”, which is also referred to dismissively in another story in the Life, but no such text has survived.

The paintings of the 1500s are more sombre and overtly spiritual in content, yet they are still marked by Botticelli’s warmth and imaginative brilliance. Paintings such as Mystic Crucifixion (1501), and Mystic Nativity (1501) have an emotional intensity that shows a deeper understanding of the tragedy of the human condition – they also show a great deal of attention given to the settings, whether it is detailed imaginary architecture or a rustic field. What became of Botticelli during this period is debated by scholars, some believing the more overtly religious subjects of his late paintings to be further evidence that he too became a follower of Savonarola. Some suggest that he was out of work towards the end of his life, as the more scientific, humanist painters such as Leonardo da Vinci came into favor. Vasari writes that Botticelli was feckless, and squandered the money he had made earlier in his career. Whatever the reason, he seems to have died a poor man.

Botticelli died in 1510, and was buried in the chapel of the Vespucci family in the church of Ognissanti in Florence, meters away from where he grew up and lived all his life. His grave is marked by a simple circle of marble.