Salvador Dalí in full Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol was a Spanish surrealist artist.

He was renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship, and the striking and bizarre images in his work.

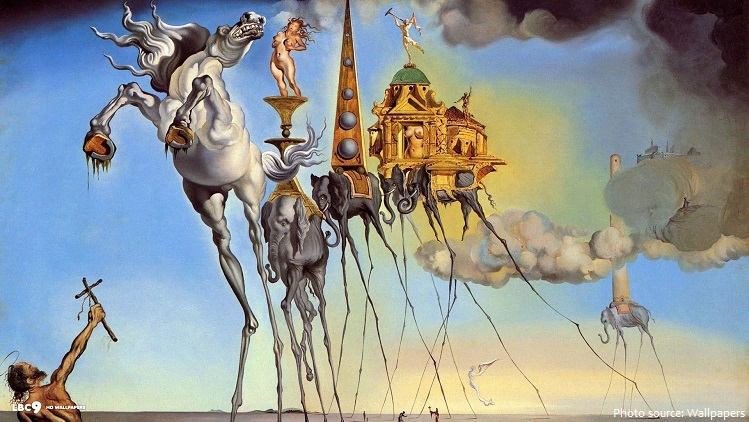

Obsessive themes of eroticism, death, and decay permeate Dalí’s work, reflecting his familiarity with and synthesis of the psychoanalytical theories of his time. Drawing on blatantly autobiographical material and childhood memories, Dalí’s work is rife with often ready-interpreted symbolism, ranging from fetishes and animal imagery to religious symbols.

The striking and somewhat bizarre images depicted in his paintings solidified his name in the Surrealist movement and his artwork is still revered by many acclaimed art critics to this day. His ambitious nature ensured that his finely honed technical skills would be extended into a vast number of mediums, as he successfully produced an array of sculptures, drawings, jewellery and furniture.

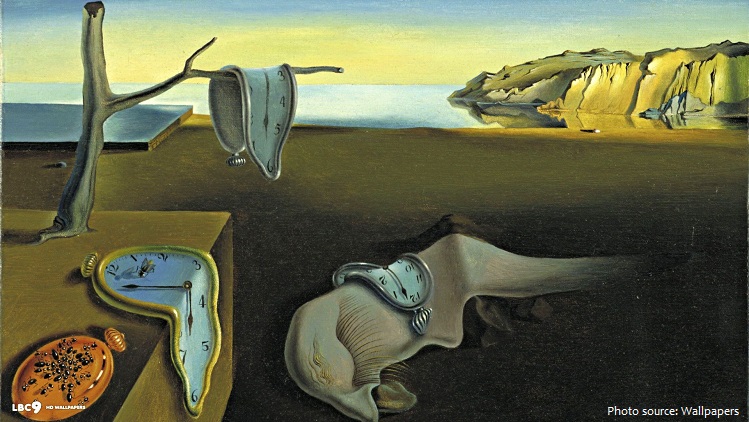

Dalí’s life-long interest in science and mathematics was often reflected in his work. His soft watches have been interpreted as references to Einstein’s theory of the relativity of time and space. Images of atomic particles appeared in his work soon after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and strands of D.N.A. appeared from the mid-1950s. In 1958 he wrote in his Anti-Matter Manifesto: “In the Surrealist period, I wanted to create the iconography of the interior world and the world of the marvelous, of my father Freud.

Food and eating have a central place in Dalí’s thoughts and work. He associated food with beauty and sex and was obsessed with the image of the female praying mantis eating her mate after copulation. Bread was a recurring image in Dalí’s art, from his early work The Basket of Bread to later public performances such as in 1958 when he gave a lecture in Paris armed with a 12-meter-long baguette. He saw bread as “the elementary basis of continuity” and “sacred subsistence”.

The egg is another common Dalínian image. He connects the egg to the prenatal and intrauterine, thus using it to symbolize hope and love. It appears in The Great Masturbator, The Metamorphosis of Narcissus and many other works. There are also giant sculptures of eggs in various locations at Dalí’s house in Port Lligat as well as at the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres.

The rhinoceros and rhinoceros horn shapes began to proliferate in Dalí’s work from the mid-1950s. According to Dalí, the rhinoceros horn signifies divine geometry because it grows in a logarithmic spiral. He linked the rhinoceros to themes of chastity and to the Virgin Mary. However, he also used it as an obvious phallic symbol as in Young Virgin Auto-Sodomized by the Horns of Her Own Chastity.

Dalí was born Salvador Felipe Jacinto Dalí y Domenech on May 11, 1904, in Figueres, Spain, located 16 miles from the French border in the foothills of the Pyrenees Mountains. His father, Salvador Dalí y Cusi, was a middle-class lawyer and notary. Dalí’s father had a strict disciplinary approach to raising children—a style of child-rearing which contrasted sharply with that of his mother, Felipa Domenech Ferres. She often indulged young Dalí in his art and early eccentricities.

As an art student in Madrid and Barcelona, Dalí assimilated a vast number of artistic styles and displayed unusual technical facility as a painter. It was not until the late 1920s, however, that two events brought about the development of his mature artistic style: his discovery of Sigmund Freud’s writings on the erotic significance of subconscious imagery and his affiliation with the Paris Surrealists, a group of artists and writers who sought to establish the “greater reality” of the human subconscious

over reason. To bring up images from his subconscious mind, Dalí began to induce hallucinatory states in himself by a process he described as “paranoiac critical.”

From the late 1920s, Dalí progressively introduced many bizarre or incongruous images into his work which invite symbolic interpretation. While some of these images suggest a straightforward sexual or Freudian interpretation (Dalí read Freud in the 1920s) others (such as locusts, rotting donkeys, and sea urchins) are idiosyncratic and have been variously interpreted. Some commentators have cautioned that Dalí’s own comments on these images are not always reliable.

In the late 1930s Dalí switched to painting in a more-academic style under the influence of the Renaissance painter Raphael.

On the brink of World War II, Dali left Paris for the US, settling in New York and California. In the US, Dali’s famously eccentric behavior made him intensely popular in the New York creative world and later in Hollywood. The couple resided in the US for eight years. Dali would turn his attention to various other means of expression beyond painting, including jewelry, textile design, sets for performing arts, and retail display windows. Some of his more notable projects include the dream sequence in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1945 film, “Spellbound”, and several window displays for the Bonwit Teller

department store in Manhattan.

Dalí returned to Spain in the late 1940s, settling in their home, the Castle of Púbol, where he expanded his painting techniques to include optical illusions, trompe l’oeil (or “fool the eye”), and larger-scale works. While he spent the rest of his life in Spain, Dali still maintained a following and fervor in the US.

In the period from 1950 to 1970, Dalí painted many works with religious themes, though he continued to explore erotic subjects, to represent childhood memories, and to use themes centring on his wife, Gala.

Two major museums are devoted to Dalí’s work: the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres, Catalonia, Spain, and the Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida, US.