Pop art is an art movement of the late 1950s and ’60s that was inspired by commercial and popular culture.

The movement was inspired by popular and commercial culture in the western world and began as a rebellion against traditional forms of art.

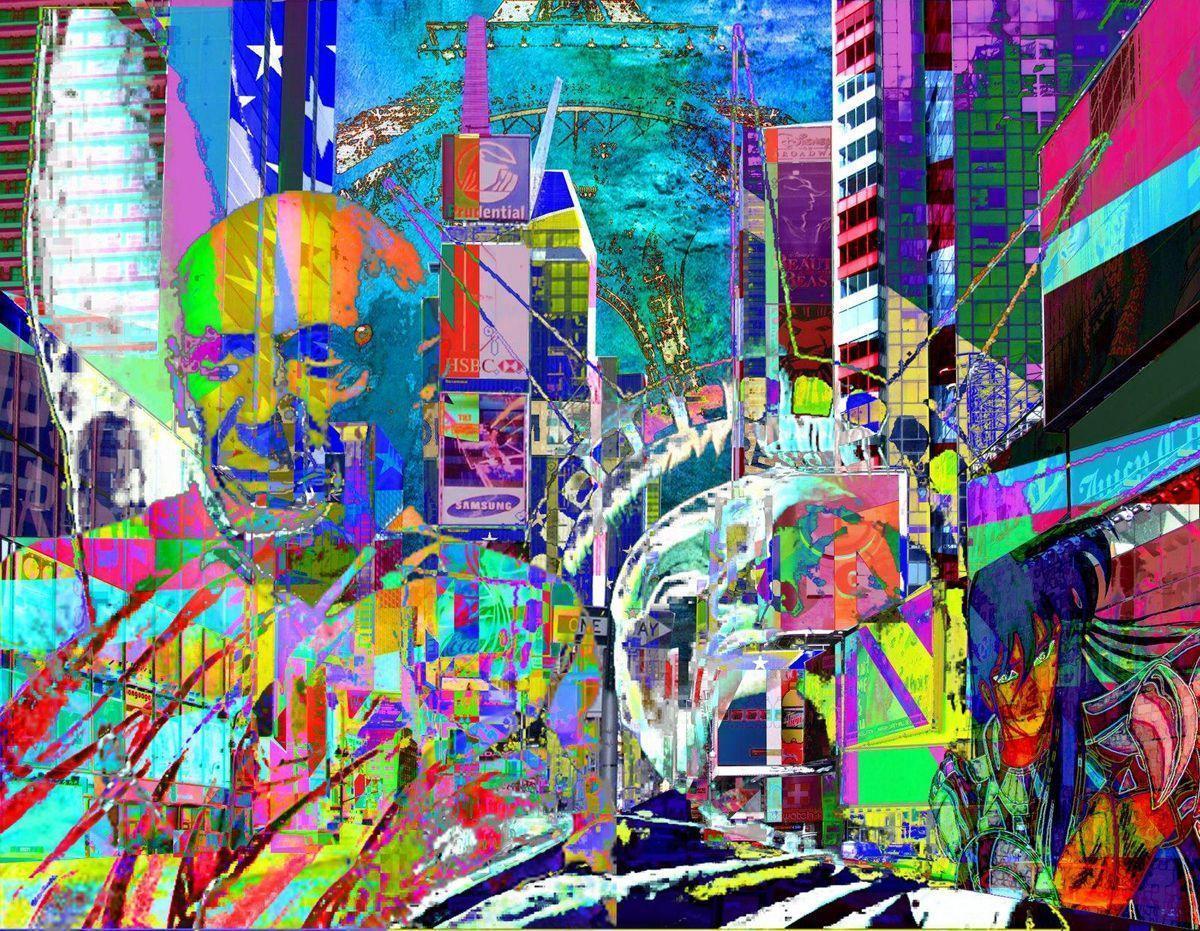

Although it did not have a specific style or attitude, Pop art was defined as a diverse response to the postwar era’s commodity-driven values, often using commonplace objects (such as comic strips, soup cans, road signs, and hamburgers) as subject matter or as part of the work.

Pop Art is often characterised by bold colours, particularly the primary colours: red, blue and yellow. The colours were usually bright and similar to your typical comic strip palette. These colours weren’t used to represent the artist’s inner world or self as they so often did in previous, classical art forms, but reflected the vibrant, popular culture around them.

In many ways, the Pop art movement began as a form of academic inquiry. In 1952–55 a group of artists, architects, and design historians met regularly at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London to discuss disparate topics such as car styling or pulp magazines. The Independent Group, as they called themselves, were committed to developing a broad-based understanding of culture from its supposedly “high” forms to its popular ones.

Emerging in the mid 1950s in Britain and late 1950s in America, pop art reached its peak in the 1960s. It began as a revolt against the dominant approaches to art and culture and traditional views on what art should be. Young artists felt that what they were taught at art school and what they saw in museums did not have anything to do with their lives or the things they saw around them every day. Instead they turned to sources such as Hollywood movies, advertising, product packaging, pop music and comic

books for their imagery.

The term Pop-Art was invented by British curator Lawrence Alloway in 1955, to describe a new form of “Popular” art – a movement characterized by the imagery of consumerism and popular culture. Pop-Art emerged in both New York and London during the mid-1950s and became the dominant avant-garde style until the late 1960s. Characterized by bold, simple, everyday imagery, and vibrant block colours, it was interesting to look at and had a modern “hip” feel. The bright colour schemes also enabled this form of avant-garde art to emphasise certain elements in contemporary culture, and helped to narrow the divide between the commercial arts and the fine arts. It was the first Post-Modernist movement (where medium is as important as the message) as well as the first school of art to reflect the power of film and television, from which many of its most famous images acquired their celebrity. Common sources of Pop iconography were advertisements, consumer product packaging, photos of film-stars, pop-stars and other celebrities, and comic strips.

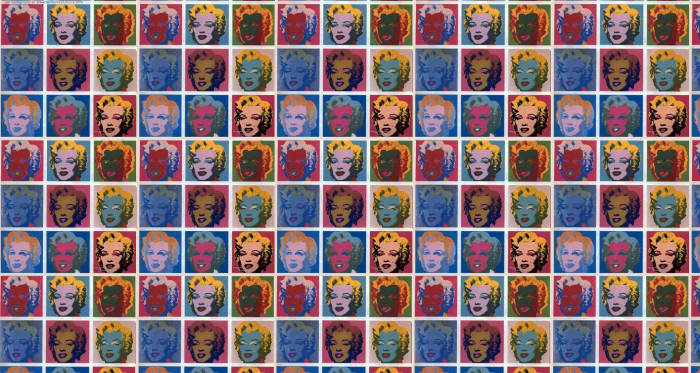

New York artists such as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, and Claes Oldenburg started defining what would become an international phenomenon, creating works inspired by mass culture, everyday objects, and the cult of celebrity in a bid to blur the lines between high-art and low-culture.

Andy Warhol understood shopping and he also understood the allure of celebrity. Together these Post-World War II obsessions drove the economy. From shopping malls to People Magazine, Warhol captured an authentic American aesthetic: packaging products and people. It was an insightful observation. Public display ruled and everyone wanted his/her own fifteen minutes of fame.

In France, Pop Art emerged in the form of Nouveau Realism defined by critic Pierre Restany as ‘new ways of perceiving the real.’ Artist Arman rejected his earlier abstract style of painting in favour of creating sculptures from found or discarded manufactured objects.

In Germany, the term Capital Realism came to define artists influenced by American Pop, founded by Sigmar Polke and including members Gerhard Richter and Konrad Lueg, who examined and dissected popular culture imagery and photography with a knowing irony.

In Japan, pop art evolved from the nation’s prominent avant-garde scene. The use of images of the modern world, copied from magazines in the photomontage-style paintings produced by Harue Koga in the late 1920s and early 1930s, foreshadowed elements of pop art. The Japanese Gutai movement led to a 1958 Gutai exhibition at Martha Jackson’s New York gallery that preceded by two years her famous New Forms New Media show that put Pop Art on the map.

Russia was a little late to become part of the pop art movement, and some of the artwork that resembles pop art only surfaced around the early 1970s, when Russia was a communist country and bold artistic statements were closely monitored. Russia’s own version of pop art was Soviet-themed and was referred to as Sots Art.

Pop art found critical acceptance as a form of art suited to the highly technological, mass-media-oriented society of Western countries. Although the public did not initially take it seriously, by the end of the 20th century it had become one of the most recognized art movements.