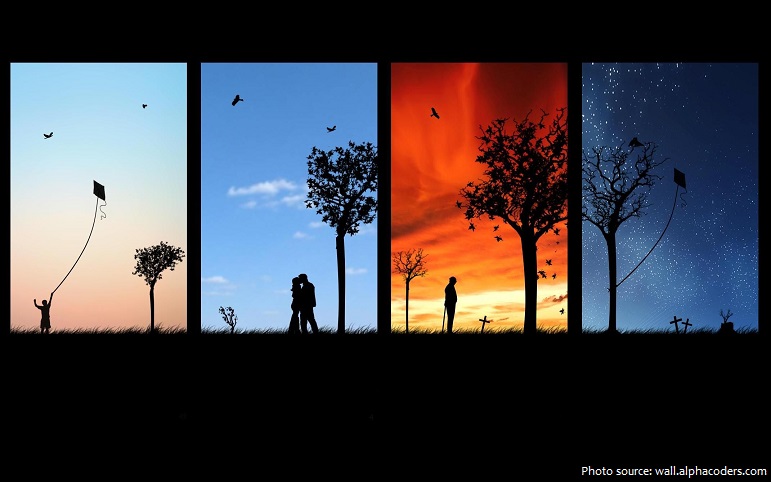

Destiny, sometimes referred to as fate is a predetermined course of events. It may be conceived as a predetermined future, whether in general or of an individual.

The very notions of fate and destiny imply a limitation of human freedom. And, while it is obvious that everyone’s freedom is limited due to circumstances, belief in fate or destiny adds the idea that there is a

preordained course of action that no personal or common effort can alter. Destiny in particular can also indicate that there is a given direction, hence a possible purpose to our lives. Nevertheless, such beliefs do not necessarily preclude humans’ free participation in fashioning their destiny—they often indicate that human actions take place within a fixed framework that hints at a certain outcome but remains open to human intervention.

The first records of the word “destiny” come from around 1300. It ultimately comes from the Latin verb dēstināre, meaning “to determine.” When destiny is used to refer to a force that controls what will happen,

it’s often thought of a cosmic or supernatural power—or it’s at least compared to one.

Fate in Greek and Roman mythology, any of three goddesses who determined human destinies, and in particular the span of a person’s life and his allotment of misery and suffering. Homer speaks of Fate (moira) in the singular as an impersonal power and sometimes makes its functions interchangeable with those of the Olympian gods. From the time of the poet Hesiod (8th century BC) on, however, the Fates were personified as three very old women who spin the threads of human destiny. Their names were Clotho (Spinner), Lachesis (Allotter), and Atropos (Inflexible). Clotho spun the “thread” of human fate, Lachesis dispensed it, and Atropos cut the thread (thus determining the individual’s moment of death). The Romans identified the Parcae, originally personifications of childbirth, with the three Greek Fates. The Roman goddesses were named Nona, Decuma, and Morta.

Although the words are used interchangeably in many cases, fate and destiny can be distinguished conceptually. Fate is strongly connected with mythology, especially that of Ancient Greece. The words has a pessimistic connotation, as it implies that one’s life course is imposed arbitrarily, devoid of meaning, and entirely inescapable. Destiny, on the other hand, is generally used to refer to a meaningful, predestined but not inescapable course of events. It is the course our life is “meant” to follow. Destiny is strongly related to the religious notion of Providence.

Distinguished from fate and destiny, fortune can refer to chance, or luck, as in fortunate, or to an event or set of events positively or negatively affecting someone or a group, or in an idiom, to tell someone’s fortune, or simply the end result of chance and events. In Hellenistic civilization, the chaotic and unforeseeable turns of chance gave increasing prominence to a previously less notable goddess, Tyche (literally “Luck”), who embodied the good fortune of a city and all whose lives depended on its security and prosperity, two good qualities of life that appeared to be out of human reach. The Roman image of Fortuna, with the wheel she blindly turned, was retained by Christian writers including Boethius, revived strongly in the Renaissance, and survives in some forms today.

The idea of a god controlled destiny plays a prominent role in various religions.

The ancient Sumerians spoke of divine predetermination of the individual’s destiny

In Babylonian religion, the god Nabu, as the god of writing, inscribed the fates assigned to humans by the gods of the Assyro-Babylonian pantheon which included the Anunnaki who would decree the fates of humanity.

Followers of Ancient Greek religion regarded not only the Moirai but also the gods, particularly Zeus, as responsible for deciding and carrying out destiny, respectively.

Followers of Christianity consider God to be the only force with control over one’s fate and that He has a plan for every person. Many believe that humans all have free will, which is contrasted with predestination, although naturally inclined to act according to God’s desire.

Within Buddhism, all phenomena (mind or otherwise) are taught as dependently arisen from previous phenomena according to universal law – a concept known as paṭiccasamuppāda. This core teaching is shared across all schools of thought, and directly informs other core concepts such as impermanence and non-self (also common to all schools of Buddhism).

The notion of karma originated in India’s religious world before becoming a household word the world over. Karma is different from destiny in that it is an application of the law of cause and effect to explain one’s lot. Karma is not presented as either the fruit of a blind will or the will of a divinity, but as the consequence of one’s very own actions. Its often used translation into everyday English is “what goes around comes around.” Yet, since the consequences of earlier actions are often long-term, even affecting later generations, in such a way that the connection between the originating cause and the consequence remains invisible and unexplained, the perception of karma often bears a close resemblance to that of destiny: for better or for worse, the course of our life is defined by more than our immediate intentions. The key difference is that the outcome is not explained in terms of a divine providence or a blind will, but in terms of earlier actions.

Amor fati is a Latin phrase that translates as “love of (one’s) fate.” It is used to describe an attitude in which one sees everything that happens in one’s life, including suffering and loss, as good. That is, one feels that everything that happens is destiny’s way of reaching its ultimate purpose, and so should be considered good. Moreover, it is characterized by an acceptance of the events that occur in one’s life.

Among the representatives of depth psychology school, the greatest contribution to the study of the notion such as “fate” was made by Carl Gustav Jung, Sigmund Freud and Leopold Szondi.